The Time Lord

Who was Severin Wunderman?

One morning in November of 2021, I woke up to my family’s group chat pinging, pinging, pinging. In the run-up to the release of Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci, the author of the book that the film was based on had given an interview to New York Magazine.

Instead of leading the conversation with discussion of the film’s subject matter or its megawatt leading lady, Sara Gay Forden spoke of another outsized figure: Severin Wunderman, my grandfather. She told a story that encapsulated his personality: in the late 1990s, she reached out to interview him for her book, to which he responded unkindly and with a threat (“I was literally shaking in my boots”). But on a second ask, backed up with more work she’d done, he responded with an invitation to interview him that month, either at his château in the south of France, or his home in London’s Chelsea neighborhood. She opted for London.

“I think I must have spent five or six hours with him. He was an incredible person. I could have written a whole other book about Severin,” she said.

Of course the family chat was going crazy – it was rare to see Severin’s name in print, thirteen years after his passing, in such a lovely way, in a major outlet. After I read the article to him, my boyfriend at the time mumbled, “you should write the book about him,” and went back to sleep. A few weeks later, as we left a screening of the film, he floated the idea again. “Why not do a project around him, around the watches?” he asked. “I just don’t know what I would say,” was my response. And there, it lingered.

Then, one day in October 2023, I found myself in the elegant Parisian home of Dominique Marny, who is the head of the Comité Cocteau – and, as the grand-daughter of Jean Cocteau’s brother, his closest living descendant. She has given me several precious pieces of advice in the short time that we’ve known each other. (She is also one of the few French women I have met who asked me about my astrological sign; as an Angeleno, that’s usually my question. For the record, she is a Pisces, Jean Cocteau a Cancer, and myself and Severin are Scorpios, making this a very watery endeavor).

We were discussing Severin’s story, the one which, despite looming large over his descendent’s lives, remains a mystery to others.

“You know what Cocteau and your grandfather had in common, Chloë?” she asked, her big blue eyes communicating that she had had a great epiphany. “They both could see what others couldn’t.”

Severin Wunderman was born November 19, 1938, in Brussels, Belgium. His family included his parents, Nathan and Helen, as well as two older siblings: a brother named Max and a sister named Bella. A Jewish family, all of them went into hiding while Belgium was under Nazi occupation, and all survived. Severin, being a toddler at the time, was hidden in the network of Dom Bruno Reynders. (It seems somewhat fitting to our family’s story that Dom Bruno was a self-described Anarchist, who at one point in his life was the personal tutor to a French Prince).

Dom Bruno placed Severin in a convent for blind children. As the only sighted child, he spent his time there leading the children around the grounds. At such a young age, he had no idea that he was hiding at all.

When the war ended and the family reunited, the time came to collect little Severin from the convent. He was most likely around seven or eight years old and had spent his entire conscious life under the care of the nuns, who, as was common during this time, were ready to convert him to Catholicism, and as such, refused to return him to his father and brother.

So Nathan and Max did what they thought was best to retrieve the youngest Wunderman, and they kidnapped him. He did not know who they were, and went kicking and screaming. When pressed for details of this decades later, Severin would say that all he could remember was seeing dead bodies covering the forest floor as his father and brother made their way through the Ardennes – the theater of war – back to Brussels.

Shortly after this traumatic event, Severin’s beloved mother passed away. Nathan, who adored his wife — despite everything, they made sure to take a walk each evening after dinner, always holding hands — fell apart. Severin’s sister, much older than he, had emigrated to Los Angeles and gotten married. (Bella by that time was in her early twenties. Her husband, Henri Zylberminc, later Harry Silvers, was a celebrated member of the Belgian Resistance).

So Severin also made his way to the United States, where Bella raised him. He used to tell us that he was “the last person to immigrate through Ellis Island,” despite the fact that Ellis Island was closed as an immigrant processing center in 1954, and is located in New York City, which is quite a ways away from Los Angeles. (In 2020, we received a genealogical report that included records of a child named Severin Wunderman passing through Ellis Island in 1950).

A handful as a child and troublemaker as a teenager, he attended Fairfax High School and worked as a valet, parking cars at the infamous Garden of Allah on Sunset Boulevard. Ever entrepreneurial, he also managed a string of paperboys.

Following a botched stomach surgery, he moved back to Brussels, where he married his first wife. They had two children, one of them my mother. In the seventies, he immigrated again to Los Angeles. (Severin married and divorced seven times, leading his children to jokingly call him ‘Liz Taylor.’ He is survived by his children Nathan, Raphaelle, Deborah and Michael, and grandchildren Justin, Sadie, myself, Josephine, Max and Maya).

Depending on the context, I have seen and heard my grandfather ascribed several identities. Belgian, American, and Jew are the most frequently used; survivor, titan, and genius have also been in the mix. By the end of his life, he was known as “The Time Lord.” Although his passport was American, I have always perceived him as European, which was also the descriptor he’d use; if someone were to calculate the total number of days in his life he spent living in the US, I am not sure that they’d outnumber the days of his life lived in his pied-à-terre in Paris, his chateau in the south of France, his offices in La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, and his home in London. And while his English was not too heavily accented, he had a tendency to quote odd, mis-translated proverbs, owing to the fact that he was a polyglot who spoke countless languages, sometimes learned via his romantic partners.

It was this immense knowledge of language that would lead to the chance of his lifetime.

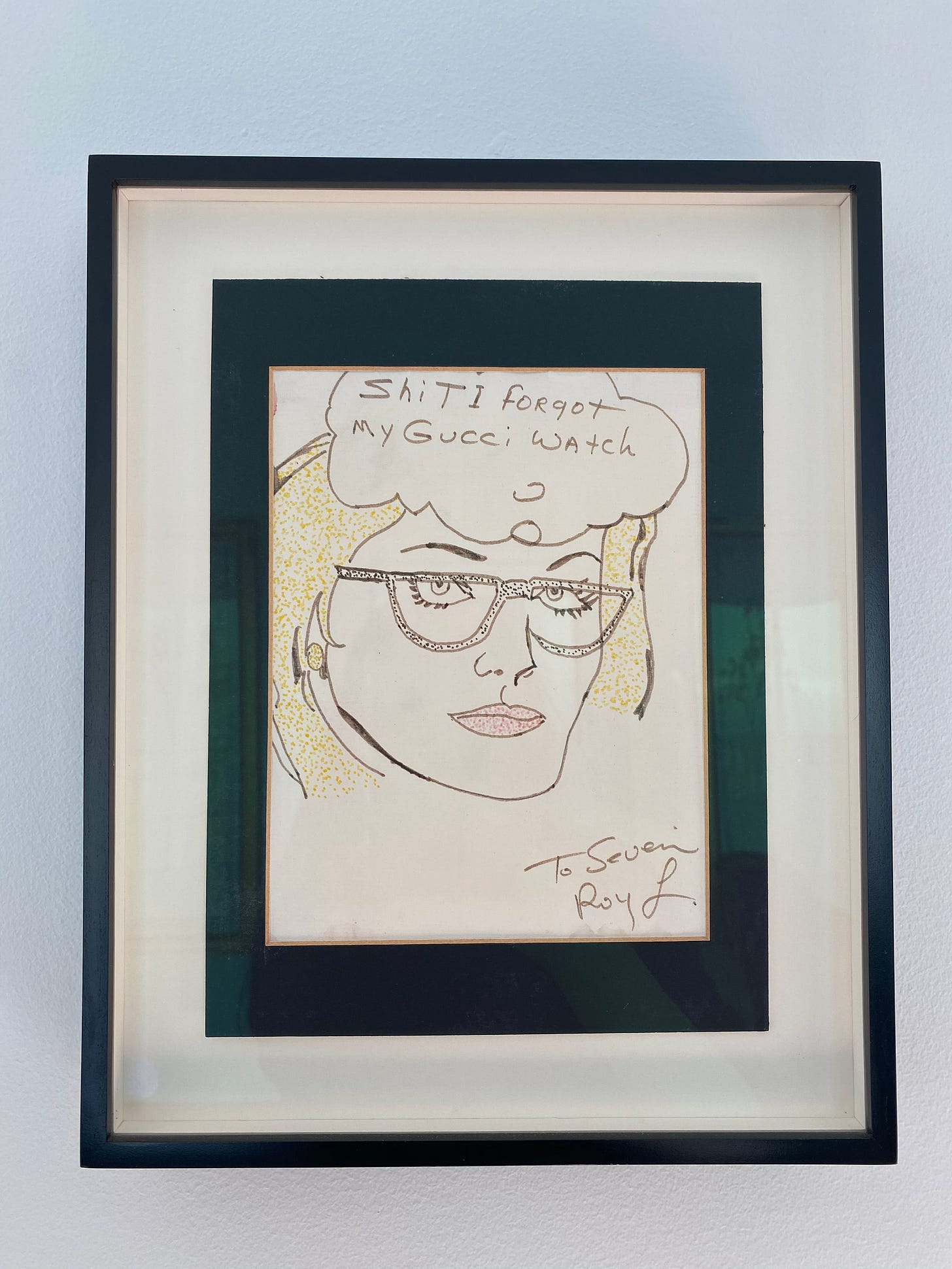

As the lore goes, Severin had an idea. He wanted to pitch Aldo Gucci, the heir and Chairman of his family’s namesake company, this: a watch, branded exclusively for Gucci, priced to entice buyers who could become legacy clients over time. While now a mainstay of luxury fashion brands everywhere, who market and sell perfumes and lipsticks as their entry products, adding watches to the mix was at the time an unheard-of concept.

Perspectives as to what happened stretch to Rashomon levels of variance – but the legend states that Severin showed up at the offices without an appointment. A phone rang, nobody was there to answer it, and Severin picked it up. Aldo Gucci, expecting confirmation of a rendez-vous he was to have that evening, was rankled by the younger man on the other end, and began to swear under his breath in the Florentine dialect of Italian that was his mother tongue.

Severin, who had picked up Florentine Italian from a girlfriend, more than understood the insults being lobbed his way, returned them and challenged Mr. Gucci to say it in person. If ever there was a Wunderman coat of arms, it would say “Qui primum ferrum eiicit, vincit” (“he who throws the first punch, wins”).

‘So he grabbed me and I grabbed him and then we both looked at each other and started laughing, and that was the beginning of my relationship with Aldo and with Gucci’ Wunderman said. [...] Wunderman would hold the Gucci watch license – the first and only watch license Gucci ever issued – for twenty-nine years. By the late 1990s, the Gucci watch business commanded sales of some $200 million a year and generated a royalty to the tune of some $30 million – providing key income to the Gucci company in its times of greatest need. (The House of Gucci, 68-69)

My grandfather revolutionized the world of timepieces; of that, there is no doubt. As mentioned in my previous essay, he would go on to put his earnings towards his collection of Jean Cocteau and his contemporaries – and to charity. Severin gave untold amounts of money to charitable causes, always under the condition of anonymity. Although he wasn’t a particularly devout Jew, he put the most weight into the mitzvah of tzedakah, often interpreting it as a directive to give without expectation of receipt – including accolades or attention. In that spirit, I will not reveal much, only that amongst his favorite causes were those dedicated to children, medical innovation, and education.

One of the few places that kept his name on the wall was USC’s Shoah Foundation, where he and his siblings gave testimonies. He also accepted the title of Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from President Jacques Chirac of France in 2004.

Which leads me back to that late Parisian morning last year, where the descendant of Jean Cocteau gave a descendant of Severin Wunderman at least one answer to a frequently asked question: “What was it about Jean Cocteau that fascinated him so much?”

Mme. Marny certainly cracked it when she said that it had to do with the eye, the ability to see what others couldn’t. Severin’s life started that way, in the most literal sense, leading those blind children around the convent; he would go on to see gaps in the market, opportunities to innovate and collaborate and where these sights settled, fortune was found. He saw the beauty and value in the life’s work of Jean Cocteau.

I recently requested Severin’s Shoah Foundation testimony from their archives and watched it for the first time in over a decade. I was astonished by many things, one of them the total and unwavering confidence that my grandfather had in himself – he knew how remarkable his life’s trajectory was, but also recounted it as if the outcomes were obvious. He described having no other option in his life but to be self-reliant, and at the same time, simply knew that his success would be inevitable because he was relying on himself.

Eyes are a motif consistent throughout the work of Cocteau. They’re highlighted on pottery, in drawings, and in his films. While his friends Buñuel and Dalí were famously slicing through one in the Surrealist classic Un Chien Andalou (1929), Cocteau’s were frequently open wide – and when shut, done so with maximum effect, and with great artistic purpose.

Cocteau’s eyes, like Severin’s, gave and received information in equal measure, as we all do. But what they were seeing was something unique and not of this world.

I’d like to leave you with a quote from John Berger’s landmark Ways of Seeing (would this be a project of art history without a Berger quote?): “The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sun set. We know that the earth is turning away from it. Yet the knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight.”

Jean Cocteau and Severin Wunderman’s lives crossed somewhere in the gray area between sight and knowledge, and with both of them dearly departed, the crossing will always remain there; where there are many stories and few hard facts.

It’s my task and my desire to dive into that gray area, to bathe in the uncomfortable ‘neither this nor that’, to share what I think and what I find in it. Perhaps, we can all come closer to finding the knowledge that exists between what is seen and what is known. It certainly won’t be boring.

***

I’m so excited to go on this journey with you. This essay was free of charge. Beginning April 2024, SACRED MONSTER will be available on a subscription basis. I hope you consider signing up for one!

If you’d like to get in touch with any questions or comments; or if there are subjects you’d like to see explored, don’t hesitate to send me a message. My email lines are open at bonjour@chloecassens.com.

À très bientôt,

Chloë Helen America Cassens

His story is ripe for a documentary! I most certainly would have that in my queue.