Welcome to SACRED MONSTER

Why I, and you, and we are here today.

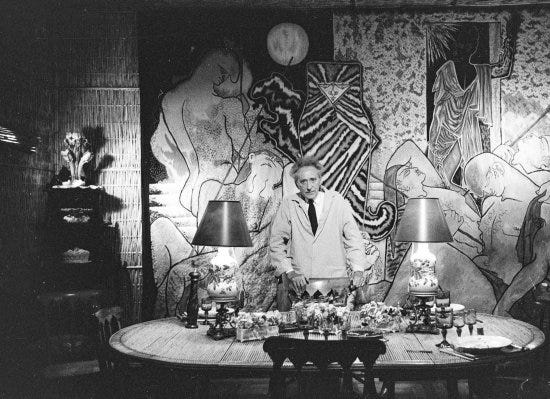

Welcome to SACRED MONSTER, a project of celebration and education around the groundbreaking French artist Jean Cocteau (1889 – 1963), his friends, and the Severin Wunderman Collection.

A SACRED MONSTER, or monstre sacré in the original French, is defined as being a celebrity whose bad and/or eccentric behaviors are forgiven or overlooked by their admirers. The term was coined by Cocteau, who originated and popularized many great and commonly used terms – he used this one to describe the Belle Epoque superstar Sarah Bernhardt.

We wring our hands over ‘unprecedented events’ – but any good student of the humanities will tell you that rarely has something never happened before. And in our current culture, we have only to look back some hundred years, to Cocteau and Bernhardt and their ilk, to see reflected back to us our own challenging times. Influencers peddling cheap ‘must-have’ products? Bernhardt lent her image to everything from bouillon to face powder. Concerns over new forms of social media? An entertainer posting an ‘incorrect’ take on Covid-19, Gaza, Black Lives Matter? You should see what the cultural movers and shakers of the early 20th century had to say about motion pictures, the Dreyfus Affair, the rise of Hitler, the Spanish Flu.

Today there are so many ‘sacred monsters’ in our cultural consciousness, that there are few to none at all. We have the desire and demand of relatability from celebrities; the capitalist nature of the aural and visual arts becoming products intended for license and franchise, sample and remake and reboot ad nauseum; and moreover, an extreme speed at which we change the focus of our attention.

There no longer exists the time, nor the space for our monsters to become sacred, for our deities to become monsters.

Which brings me back to the star of this show: Jean Cocteau.

It is highly likely that you’ve heard or read about him in the same breath as one of his contemporaries: Marcel Proust, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Serge Diaghilev, Coco Chanel, and Elsa Schiaparelli are just a few of the household names.

But to know Jean Cocteau’s work, or be familiar with who he was, is to begin to understand how utterly vital, totally influential, and beyond definition his place is in the history of art – and the 20th century. I have been studying and researching Cocteau for most of my life, and still feel awed by the breadth and depth of material Cocteau left with us when he passed away in 1963.

Jean Cocteau burst into the Parisian social and creative scene at the age of sixteen, and remained at its beating heart until he passed at the age of seventy-four. He was not a member of any set movement, but collaborated, socialized, loved, and was involved with many you may have heard of: the Fauvists, Dadaists, Surrealists, Modernists, the Ballet Russes, and the Avant-Garde all came and went from his orbit.

Cocteau was unique for many reasons, one of which being the fact that he was an artist who excelled in almost every medium he chose to work in, which was almost every one you can think of. Depending on where you live and what education you received, you may know Cocteau only or primarily as a filmmaker; poet; playwright; muralist; writer; or fine artist. One of his most mainstream claims to fame is that he was the first to commit La Belle et la Bête to celluloid, which heavily inspired Disney in their adaptation of the classic fairy tale many decades later.

Cocteau is known as ‘The Poet’ – a title he adopted and insisted on using himself. While traditional written poetry was the first medium through which he worked, he would go on to call all of his works poetry of their respective mediums: ‘poésie de théâtre,’ ‘poésie de roman,’ ‘poésie graphique’ and so on, and so forth.

Thematically, his work was transgressive (he never hid his homosexuality), provocative, fantastical, and marked by what I find is a tender vulnerability unique to Cocteau. I never come away from one of his pieces feeling alienated, but rather, awed by the humanity of his work.

You may be wondering who I am.

My full name is Chloë Helen America Cassens. I lived as a child in Switzerland, was raised in Los Angeles (where I was born), and received my B.A. in Comparative Literature at Barnard College in New York City. I started working at fourteen years old, at a club on the Sunset Strip called the Roxy Theatre; DJed on WBAR and DASH Radio; and spent a lot of my life backstage, being both related to, and a lover of, musicians.

All the while, I was devoted intellectually to a dead, queer, French artist. But this devotion was, and is, my birthright.

You may cry “nepo baby!” – but I come by it honestly. I am not sure I’ve taken this job from someone more deserving, as I don’t think anyone else could do it.

My grandfather was a man named Severin Wunderman. A survivor of the Shoah, his life’s trajectory took him from an early childhood hidden from Nazis in the Belgian countryside to an adulthood marked by incredible hard work and equally hard-won fortune: he created, licensed and manufactured Gucci Timepieces. He was so successful that his branch of the company kept the financially struggling mothership afloat for years – long enough to become the juggernaut it is today.

All the while, he was enchanted by the art of a certain dead, queer, French artist.

At the time of his death in 2008 – and this writing – the Severin Wunderman Collection was, and remains, the largest collection in the world of Jean Cocteau. It started when he was nineteen years old, with a simple drawing he spent his week’s wages to acquire when he spotted it in a shop window; it ended in Menton, France, in the official Musée Jean Cocteau-Collection Severin Wunderman, where it lives presently.

One morning, when I was around nine or ten years old, my grandfather told me to finish my breakfast and meet him in the entry of the house with paper and pen. He proceeded to tell me that our project for the summer was going to be one of education: he walked me through each piece of art in the house, telling me what it was, why he had it, and I would take notes.

I should mention that the house in question was, in fact, a François I-era Chateau in the South of France, complete with a dungeon, an original mural wrapping around a spiral staircase, a little room at the top of a turret, the whole nine yards. It was a lot of rooms, and even more art, to cover in my Lisa Frank neon-unicorn-adorned notebook. I loved every minute of it – spending time with my grandfather, who I adored, and sharing this topic for which he had an obvious excitement.

Severin’s birthday was the 19th of November, and mine, the 20th; we were both born under the sign of Scorpio, a fact that he used to remind me of often. When we were in a crowd, he would remind me sotto voce that while he was the ‘Big Scorpion,’ I was the ‘Little.’ “Remember, it’s usually the smaller ones that are the most dangerous,” he’d say.

I would go on to write two pieces of research centered around Cocteau; and yet, I would not decide to get into the field full-time until I was in my late twenties – and working at a multimedia company that provides sex education.

In the dead of night and under a full moon, I suddenly woke from a deep slumber with the realization that somebody needed to carry the Jean Cocteau, Severin Wunderman flag. And that somebody could be me.

I was already focusing on educating people around porn literacy, masturbation, and cybersecurity regimens. Why not apply it towards educating people on a subject I had been living with, in such a unique way, for my whole life?

Which brings us back to SACRED MONSTER. For too long, Jean Cocteau has not been in the consciousness internationally – almost always a footnote, a ‘friend-of’ in Bravo TV parlance. He is one of the most counterfeited artists in French history, with an insurmountable and increasingly unknown influence on culture today. He is your icon’s icon. (Or, perhaps, your icon’s icon’s icon).

There is a harmoniousness to the idea that Jean Cocteau, in originating a term to describe the transcendence of a public figure, would some day come to embody that idea himself; I doubt the thought didn’t cross his mind at one point in his later years.

I promise that SACRED MONSTER will be academic, yet accessible; cerebral, yet charming. If I’m successful, you’ll come away each month feeling a bit smarter, which can’t hurt.

“Je reste avec vous,” is Cocteau’s epitaph. Stay, he has, and stay, he will.

***

I’m so excited to go on this journey with you. This essay, as well as the next, will be accessible free of charge. Beginning April 2024, SACRED MONSTER will be available on a paid subscription basis. I hope you consider signing up for one!

If you’d like to get in touch with me with any questions or comments; or if there are subjects you’d like to see explored, don’t hesitate to send me a message. My email lines are open at bonjour@chloecassens.com.

À très bientôt,

Chloë Helen America Cassens